Denis Doulgeropoulos

Your Financial Professional & Insurance Agent

Preparing for Libor to Leave the Building

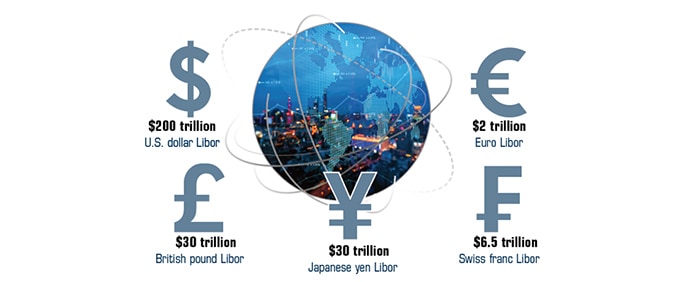

The London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor) — once called the world’s most important number — is an interest-rate benchmark that has influenced borrowing costs for consumers, businesses, and investors around the world since 1986.1–2 From daily banker submissions, it has been quoted in five currencies (the British pound, the Swiss franc, the Euro, the Japanese yen, and the U.S. dollar).

Because Libor is based on quotes instead of actual transactions, it’s possible for banks to manipulate interest rates to their advantage. A 2012 scandal exposed widespread market manipulation, and Libor is believed to have worsened the 2008 financial crisis. As central banks slashed benchmark interest rates to help reduce borrowing costs and support the global economy, Libor rose instead.3

It’s a monumental task, but industry regulators are working on replacing Libor with a more reliable benchmark to strengthen the global financial system. U.S. dollar Libor still determines the interest rates on more than $200 trillion in financial products, including private student loans, credit cards, adjustable-rate mortgages, business loans, and a wide array of securities and insurance contracts.4

Deadline Looms

Some Libor settings will stop being polled and published at the end of 2021, but others will continue to be available until June 2023, so most legacy contracts can mature before Libor is fully retired. As a result, U.S. regulators told financial institutions not to issue new financial contracts based on Libor after December 31, 2021, though they may continue to reference it for many existing debts until June 30, 2023.5

The Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) is a working group of private market participants, such as banks, insurance companies, and asset managers, convened by the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In 2014, the ARRC identified and addressed transition issues and analyzed potential alternative rates, and in 2017 endorsed the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) as the new preferred benchmark rate. Since then, ARRC has been facilitating an orderly transition by encouraging adoption of SOFR, recommending best practices, developing SOFR markets, drafting fallback clauses, proposing legislation to reduce legal uncertainty for legacy contracts, and publishing industry progress reports.

Subject to Change

Face value of financial products benchmarked to Libor, by currency

New Benchmarks

Financial instruments previously tied to U.S. dollar Libor will instead be linked to SOFR. Per the ARRC, SOFR is a “nearly risk-free” reference rate that is fully based on transaction data from the U.S. Treasury repurchase agreement (repo) market. SOFR was recommended because it is suitable for use in most financial products and has much larger underlying transaction volumes than other Libor alternatives.6

Other central banks have recommended their own benchmarks to replace Libor, including the reformed Sterling Overnight Index Average (SONIA) in the United Kingdom.

Depending on the product, financial institutions may reference alternative rates that are “credit sensitive,” since they may better reflect lenders’ funding costs. However, regulators have warned that switching to benchmarks other than SOFR may present similar risks to financial market stability as Libor.7

For the many financial institutions that are moving away from Libor, moving to replacement rates is a complicated and costly process. They must analyze their exposure, adjust valuation and risk models, update contracts, communicate with clients, and meet reporting requirements. It’s estimated that transition costs will exceed $100 million for each of the major banks in 2021 alone.8

Businesses and consumers with adjustable-rate loans based on Libor should pay attention to their lenders’ communications regarding changes to reference rates. In the future, switching to a different index might result in a higher base rate and higher borrowing costs.

1, 4) Bloomberg, January 28, 2021

2–3) Forbes, August 10, 2021

5–6) Alternative Reference Rates Committee, 2021

7) The Wall Street Journal, August 16, 2021

8) Bloomberg, February 5, 2021

This information is not intended as tax, legal, investment, or retirement advice or recommendations, and it may not be relied on for the purpose of avoiding any federal tax penalties. You are encouraged to seek guidance from an independent tax or legal professional. The content is derived from sources believed to be accurate. Neither the information presented nor any opinion expressed constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. This material was written and prepared by Broadridge Advisor Solutions. © 2022 Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc.